The Feast of the Transfiguration

"We know that when he appears we shall be like him” (I John 3:2).

In the Orthodox Church, August 6 is the Feast of Christ’s Transfiguration. It recalls an astounding incident that is reported by Matthew, Mark, and Luke, so we know it made an impression. Jesus took his closest disciples, Peter and James and John, and led them up the side of “a high mountain.” Here’s how St. Matthew tells the story:

[A]fter six days Jesus took with him Peter, James and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain apart. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his garments became as white as light. And behold, there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him.

Peter said to Jesus, ‘Lord, it is well that we are here; if you wish, I will make three booths here, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.’ He was still speaking, when lo, a bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice from the cloud said, ‘This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.’

When the disciples heard this, they fell on their faces, and were filled with awe. But Jesus came and touched them, saying, ‘Rise and have no fear.’ And when they lifted up their eyes, they saw no one but Jesus only. (Matthew 17:1-8)

Perhaps these three disciples were used to being taken aside for private conferences. But they weren’t prepared for what happened that day. They saw Jesus “transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun.” They saw Moses and Elijah speaking with him. Peter began to babble the first excited thing that popped into his head. That’s when a “bright cloud” overshadowed them, and they heard the Father’s voice.

No wonder they tumbled to the ground in awe. And when Jesus came and touched them, saying, “Have no fear,” they looked up to find they were alone.

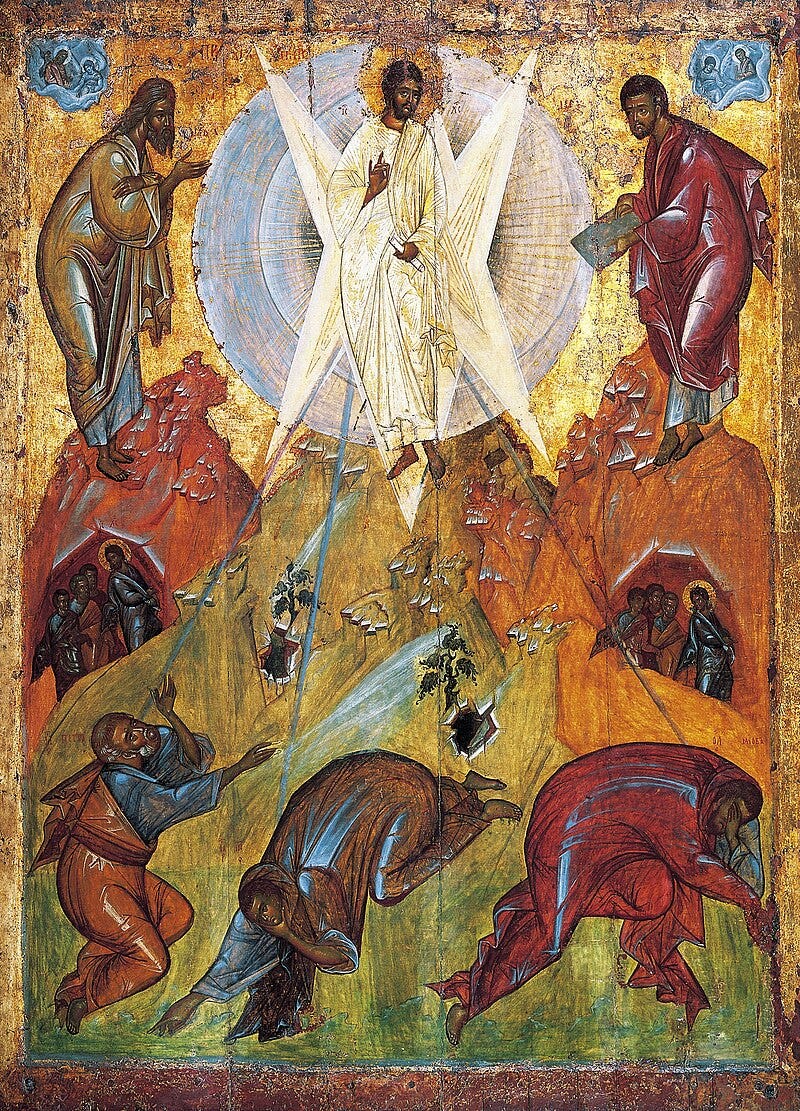

This mosaic icon, above, fills the apse over the altar in the monastery church of St. Catherine on Mt Sinai. No one knows how old the monastery is; even in the 300s, pilgrims encountered hermit monks living in mountain caves. But they were often attacked by Bedouins, so in AD 550 the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire built a monastery with walls 40 feet high. It has functioned as an Orthodox monastery ever since; prayer and worship has been offered there every day.

In this icon we see Christ standing in the center, transfigured in glory. Elijah stands in midair on the left and Moses on the right, both in stances that suggest lively conversation. Below Moses and Elijah, along the bottom edge of the image, we see John on the left, falling to his knees with his hands raised in prayer. John’s brother James, on the other side, also kneels and seems to cower before the overwhelming sight. Beneath the feet of Christ, Peter has fallen prostrate. A moment before this he had been sputtering about building booths for the three holy figures to occupy.

But the power of the icon comes from Christ himself, filling the center of the image, gazing out steadily with authority and love. White rays streak out his dark blue mandorla, an oval space which seems to recede back into eternity, to the foundation of the universe. And the central fact of the story is that Christ is glowing. He is turning into light. What can that possibly mean?

Peter and John, two of the eyewitnesses that day, wrote letters afterward that are included in our New Testament. We can gather some hints as to what they made of it. It seems, understandably, to have made a big impression.

In his second letter, Peter retells the story:

[W]e did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty. For when he received honor and glory from God the Father, and the voice was borne to him by the Majestic Glory, "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased," we heard this voice borne from heaven, for we were with him on the holy mountain. (2 Peter 1:16-18)

St. John begins his intricately woven first letter with a similar claim to have been an eyewitness:

“That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our own eyes…This is the message we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light and in him is no darkness at all.” (1 John 1:1, 5)

God is light. Throughout the Scriptures, God appears repeatedly in the form of overwhelming light. A bright cloud covers the mountain top when Christ’s glory is revealed, just as a cloud shook Mt. Sinai with lightning when Moses spoke with God. When Moses descended the mountain carrying the tablets of the Law, his face was shining from the presence of God: “The Israelites could not look on Moses’ face, because of its brightness” (2 Corinthians 3:7). When the Israelites were in the wilderness, they were led by pillars of cloud and of fire. When St. Paul was on the road to Damascus, he was overwhelmed by “a light from heaven, brighter than the sun” (Acts 26:13).

But there is something about light that most previous generations would have known, that doesn’t occur to us today. We think of light as something you get with the flip of a switch. But before a hundred years ago, or so, light always meant fire. Whether it was the flame of a candle, an oil lamp, a campfire, or the blazing noonday sun, light was always produced by fire.

And fire, everyone knew, must be respected. That would be one of the lessons learned from earliest childhood. Fire is powerful and dangerous. It does not compromise. In any confrontation, it is the person who will be changed by fire, and not the other way round. As Hebrews 12:29 says, “Our God is a consuming fire.”

So when you see a reference to light in any ancient text, always remember that the author expected you to picture fire. When the Bible says, “God is light” (1 John 1:15), we shouldn’t picture a table lamp. St. John had something more dangerous in mind. We approach God with reverent awe, the holy fear the Psalmist means when he says “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Psalm 111:10).

Yet this consuming fire was something God’s people yearned for. In some mysterious way, light means life. John tells us, “In him was life, and the life was the light of men” (John 1:4). Jesus says, “I am the Life” (John 11:25), and also “I am the Light” (John 8:12).

Light is life: we live in light, and couldn’t live without it. In some sense, we live on light. It is light-energy that plants consume in photosynthesis; by means of their chlorophyll molecules, they take light and transform it into their own substance. It’s an everyday miracle that’s as mysterious as life itself.

And when we eat those plants, or eat the animals that eat plants, we are feeding, secondhand, on light. Light is converted into life, literally, with every bite we eat. God designed us to live on light. The fire of God consumes us, and we consume it as well. “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man, and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (John 6:53).

Peter is writing his letter on the far side of everything—the Last Supper, the campfire denial, the Resurrection, and the Pentecost outpouring. He’s writing and trying to make sense of what happened that day on Mt. Tabor, so many years before. He saw God’s glory, but he’s also sure that, in some mysterious way, this glory is meant for us as well. We’re called to partake of God’s glory.

His divine power has granted to us all things …[and] called us to his own glory, that …you may escape …the corruption that is in the world…and become partakers of the divine nature. (2Pe 1:3-4)

“Partakers of the divine nature.” The life that is in Christ will be in us.

Now, we may be tempted to take such statements metaphorically. When St. Paul refers to our life “in Christ” over 100 times, we might assume he means a life that looks like Christ’s. But it seems Peter meant something more immediate and more radical: true oneness with Christ. We will partake of, consume, the light of Tabor and the life of Christ. We will receive, not mere intellectual knowledge of God, but become bearers of God’s presence.

This is the distinctive thing that Eastern Christianity brings to our common Christian life. The Eastern Church assumes that the purpose of Christian life is to become one with God. That’s not just for mystics; it is an invitation held out to every Christian, or rather, to every human being. What Eastern Christianity can bring to the West is 2000 years of experience in how to do this, how to safely and with good discernment live in Christ in quite a literal way, so that his light in us is always increasing.

The Greek term for this process of increasing participation in Christ is theosis. It’s a word that is usually translated “deification” or “divinization,” but they’re not quite right; they make it sound like we expect to become junior gods, each with our own miniature universe. No, theosis means being saturated by God’s presence, God filling us up with his light.

We can take the Greek word apart, theosis, and see that it’s composed of theos, which means “God,” and the suffix –osis, which means a process—metamorphosis, tuberculosis, osteoporosis. Osmosis: as red dye saturates a white cloth by the process of osmosis, so humans can be saturated with God’s presence by the process of theosis.

St. Athanasius, writing about AD 320, said, “He was made man so that we might be made god.”[i] And this is God’s intention for every single human life. St. John’s Gospel says, “The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world” (John 1:9).

This process requires simplicity and humility. We are gradually and thoroughly absorbed through daily, diligent self-control. Through prayer, fasting, and honoring others above self, we gradually clear away everything in us that will not catch fire.

For we are made to catch fire. We are like lumps of coal, dusty and inert—not much to boast about. But we have one innate ability: we can burn. You could say that it is our destiny to burn. God made us this way, because he designed us to bear his light. And when that happens, Jesus says, “your whole body will be full of light” (Matthew 6:22).

In the next life we will all be in the presence of God. We are in his presence now, but it is veiled by creation, and in the next life the veil is taken away. What will that unveiled presence be like?

Someone who loves God will find that all-pervading light to be like a fountain overflowing with life and joy, and know firsthand what it means to say “God is love” (1 John 4:8, 16). But one who, as St. John’s Gospel says, “loved darkness rather than light” (John 3:19), will find the inescapable light to be misery and destruction. Christ’s light will be to them a paradoxical darkness, an “outer darkness,” as Jesus said, where “people will weep and gnash their teeth” (Matt 8:12, 22:13, 25:30).

God is always love. He is always light. He is always fire. People can experience that fire in different ways, depending on whether they welcome or reject him.

It’s not only a spiritual transformation; it’s physical as well. St. Paul says that our bodies will “bear the image of the man of Heaven” (I Corinthians 15:49). That means this body, this very same too-familiar body, that embarrasses and disappoints, that is marred by flaws and flab, is one day going to be, it says in 1 Corinthians, “raised in glory” (1 Corinthians 15:43). As St. Paul says in Colossians, “Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Col 1:27)

St. John is perhaps reflecting on what he witnessed on Mt. Tabor when he writes: “It does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when he appears we shall be like him” (I John 3:2).

And yet what they saw that day was only a portion of Christ’s true glory. The Troparion of the Transfiguration, written in the 700s, says:

You were transfigured on the mountain, O Christ God, revealing Your glory to Your disciples as far as they could bear it. / Let Your everlasting Light shine upon us sinners, / through the prayers of the Theotokos. / O Giver of Light, glory to You!

What the apostles saw was not even all of Christ’s glory, but just the amount that they could bear to see.

In fact, while we call it Christ’s Transfiguration, it wasn’t Christ who changed. He is always radiant with glory. It was the eyes of the apostles that were opened, so they could get a glimpse of the reality that had been with them the whole time—but only a glimpse, only what human body and mind could bear.

Both St. Peter and St. John, writing their letters long after these events, said that Christ’s glory will be ours as well. If this is true, we’re going to have to change. If it is God’s plan to fill our souls and bodies with his blazing-diamond life, we must decide whether we are going to cooperate.

If we do, we’ll have to teach ourselves to “pray without ceasing” (I Thessalonians 5:17), gazing constantly on God who dwells in our hearts, focused on him, as the Psalmist says, “as the eyes of servants look to the hand of their master” (Psalm 123:2).

We’ll have to learn to love others the way that Christ loves them; to always remember that every other human being we encounter, no matter how exasperating, is a recipient of this invitation from God, that every person we meet is designed to blaze up with glory. Like Peter, James, and John, we’ll fall down before the Lord in fear and trembling, driving out all the triviality and self-satisfaction that threaten to choke our lives. Once we decide to start that journey we’ll find that it never ends; like the children at the end of Lewis’s Narnia stories, we will always be discovering more, going “further up and further in.”

We supply the coal, God supplies the fire. As St. Paul said, “So work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for God is at work [energizing] in you” (Phillipians 2:12).

Where are we going? We’re all going up Mt. Tabor. “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another” (2 Corinthians 3:18).

Saturate me, Lord Jesus. Emblazon me as you did the bush on Mount Horeb.

This was wonderful!