St. Paisios and the Alcoholic Monk

Repentance is enough to clear the way to God

I found a link for the story of St. Paisios and the alcoholic monk! Better told than in my haphazard summary.

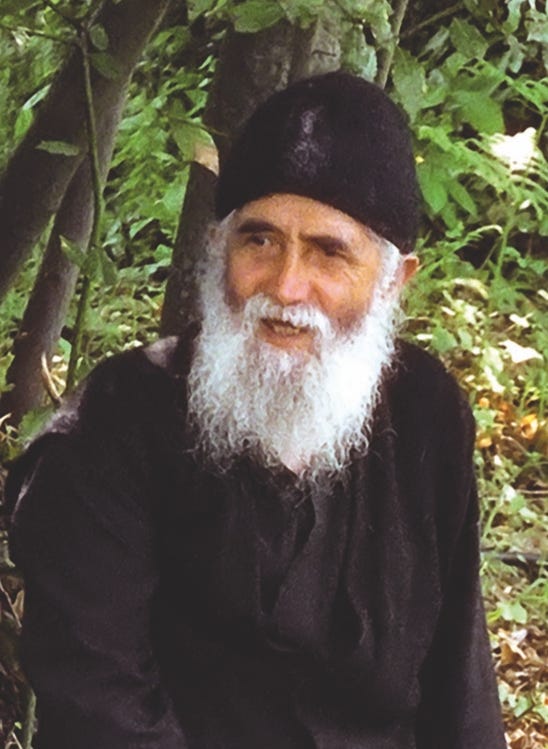

There’s no image to go with this story, so I’ll add a photo of St. Paisios.

I think I don’t know how to use Substack notes yet. I sent out something last night about God not being wrathful, but simply too overwhelming for humans to withstand, so to speak. Since then I’ve been responding to comments, and sometimes posting comments as new Notes, and it is probably a big mess, if you’re trying to follow a thought.

So God is not wrathful at us for our sins. We automatically fear that, reasonably enough because we are mere creatures. We can’t imagine not being angry, if we were God. But it’s not in his nature to snap into anger.

God hates sin like the parents of a leukemia victim hate cancer.

He does not have alternating emotions—being pleased with person A and wrathful at person B. That’s a childish idea, and it may have been planted in you as a child and caused great sadness, so I hope you can recognize what’s going on when those thoughts pop up and root them out.

The list of sins we commit is not determinative of salvation, as long as we repent. As long as you are sorry for your sins and yearn to be at peace with God—well, that’s his own love for you coming back out of you, completing the circuit, uniting you with him. It’s remaining near God in repentance and humility that prepares you for eternity in his presence.

I’m sorry that this concept of bad deeds being like speeding tickets, and you have to pay the price, is so widespread. God forgives our sins without needing to be repaid. All we need is repentance. All we need is love and longing for him.

I wanted to share this story told by St. Paisius, to show how even scandalous sin does not cost someone salvation, if they are repentant and longing to be free from sin, and longing to be near God. Gosh I wish I could find the original for this story, but this is how I remember it going.

He said that there was a monk at his monastery who got drunk every day. He drank vodka, many glasses, and was visibly inebriated. Naturally, this distressed pilgrims to the monastery.

But Paisios learned, in talking with the monk, that when he was a baby there were raids by Turks to kidnap Christian boys and raise them as slaves. When his parents went out in the fields to work, they would take him along, and put vodka in his bottle to keep him quiet.

Thus this child grew up drinking every day. Paisios asked him how many glasses he drank each day, and he said about 20. So Paisios said, could you cut it back a little? One glass less, and then another, as time went by?

And so that is what the monk did. When he died, he was still getting drunk every day. But he had cut back on the number of glasses bit by bit, gaining a partial victory, an offering to God, the best he could give.

Can you see that God would not be wrathful at that monk?

It’s not about sins as specific, discrete bad deeds. It’s about our attitude toward God. The road to Paradise is repentance; every sin can be forgiven, if you truly repent.

"The spiritual life is this,” a monastic elder from the Egyptian desert once said, “I rise and I fall. I rise and I fall.”

You've touched on what to me is the most interesting doctrinal nuance between the Christ East and the West:

Roman Catholicism views sin primarily through a juridical lens—personal acts that incur guilt, with humanity inheriting both the guilt and the consequences of Adam’s sin—while Eastern Orthodoxy sees sin as a therapeutic tragedy: a sickness and corruption inherited from Adam that brings mortality and a bent toward sinning, but not personal guilt for Adam’s act.

It seems to me that these two paradigms weren't always in tension as they seem to be now. Rather, they coexisted without tension in the early Church, most perfectly blended in St. Irenaeus of Lyons, who taught that Christ both pays the just debt owed because of Adam and heals the mortal, corrupted nature Adam left us. In my pre-Catholic days (back at a Reformed seminary, Frederica when--as it happened--I first discovered your books!), I developed a real love for Irenaeus and now I think I know why. :)