It is the feast of St. Moses the Ethiopian today, who is much beloved among American converts. He always brings to mind this anecdote, from the early centuries of the Church, when Christians were going into the desert in order to “pray without ceasing.” (That’s something St. Paul exhorts in epistles to four different communities.) Here’s how I tell the story in my book Welcome to the Orthodox Church.

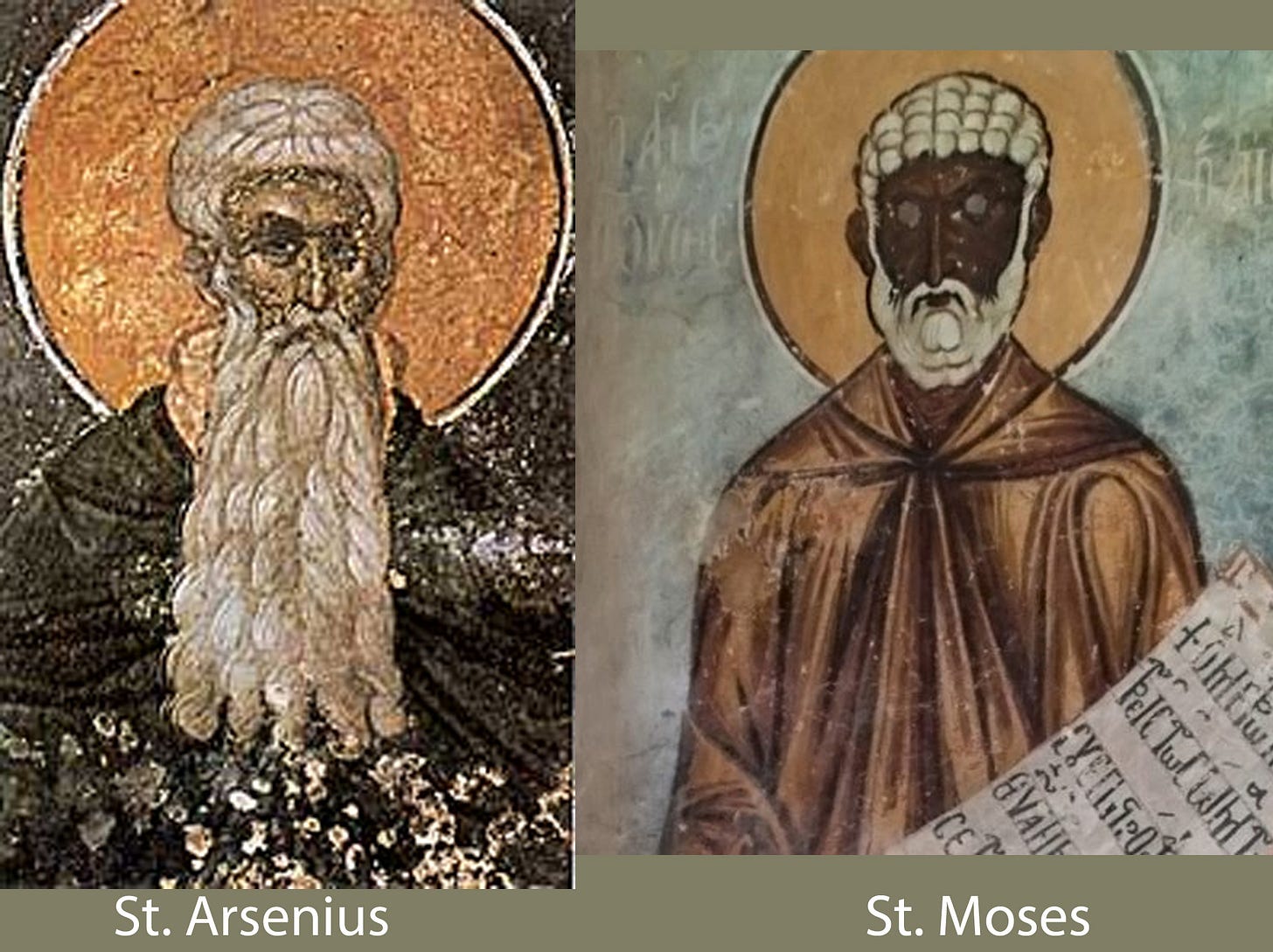

There’s a story of the Desert Fathers concerning two monks who went to visit some of the luminaries of that age. First they went to see the famed ascetic Abba Arsenius. He had been a wealthy senator in Rome, and was known for his profound humility, sobriety, and penitence. (It is said that noble, silver-haired Arsenius was very handsome, except that he had wept for his sins so long that his eyelashes had washed away.) The two monks traveled a long way to get to his rustic cell, but once they had greeted the old man and sat down, silence reigned. The monks began to feel uneasy and took their leave.

Next they decided to see another giant of the desert, the former gang leader Abba Moses. This large, physically powerful man had been a robber and murderer before coming to Christ. “The Abba welcomed them joyfully and took leave of them with delight,” a very different reception than they’d had from Arsenius.

When the monks returned and told about their journey, a fellow monk who heard the story was puzzled by the difference between the two holy men. “He prayed to God saying, ‘Lord, explain this matter to me: for Your name’s sake one flees from men, and the other, for Your name’s sake, receives them with open arms.’” This prayer was answered by a vision. “Then two large boats were shown to him on a river, and he saw Abba Arsenius and the Spirit of God sailing in one, in perfect peace; and in the other was Abba Moses with the angels of God, and they were all eating honey cakes.”

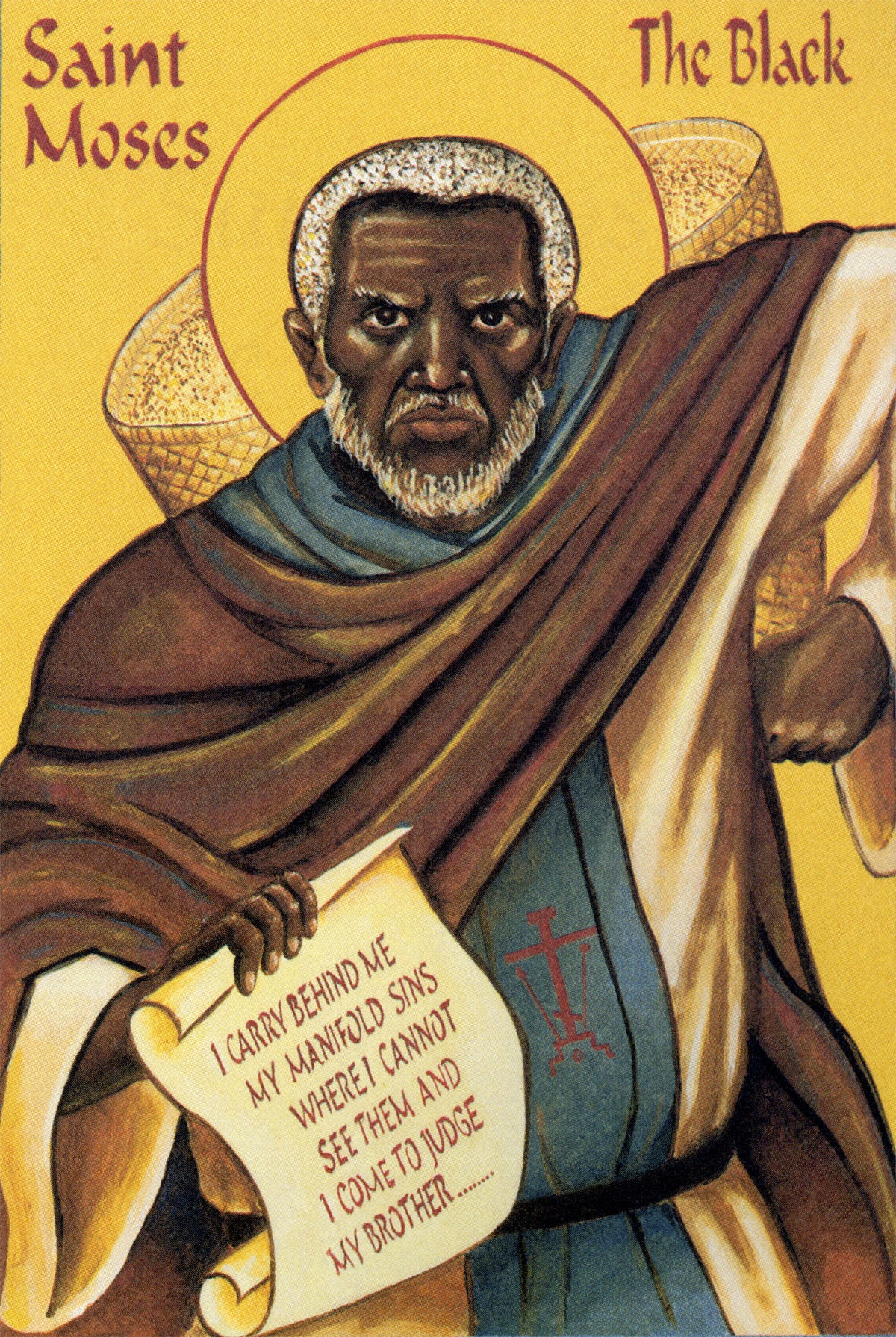

About the image below: a favorite story about Abba Moses is that a monk in his monastery had seriously broken one of the community’s rules, and a meeting of all monks was called to decide what should be done. Moses arrived with a basket (or sack) on his back, with a hole in it, and the wheat (or sand) was trickling out behind him. He said (variously phrased): “Here I come to judge my brother, while my own sins run out behind me, where I don’t see them.”

Though this style of icon doesn’t appeal to me (too emotional), I want to show you the variety of styles in painting icons. Every culture works out it’s own most-appropriate, most-effective style of painting icons, and America will do so as well. But there’s a paradox about a culture discovering its own best icon-style, because it would be unhelpful to cultivate a style that was familiar and comfortable. An icon needs to be somewhat strange, calling us away from the usual. St. Moses left behind everything he was familiar with, when he became a monk—but without rejecting the elements that were his best self, that could serve the community well, like his great physical strength and his cheerful hospitality. Our own best selves, unique, will shine in Paradise.

I agree, one of the things that is so great about the Church is that saints can become holy while still being themselves. Introverts don't have to become extroverts, but can use silence and stillness to pray while extroverts warmly welcome all with words. St. Peter remains boisterous, St. Paul remains studious. What Christ does is make us the True versions of ourselves.